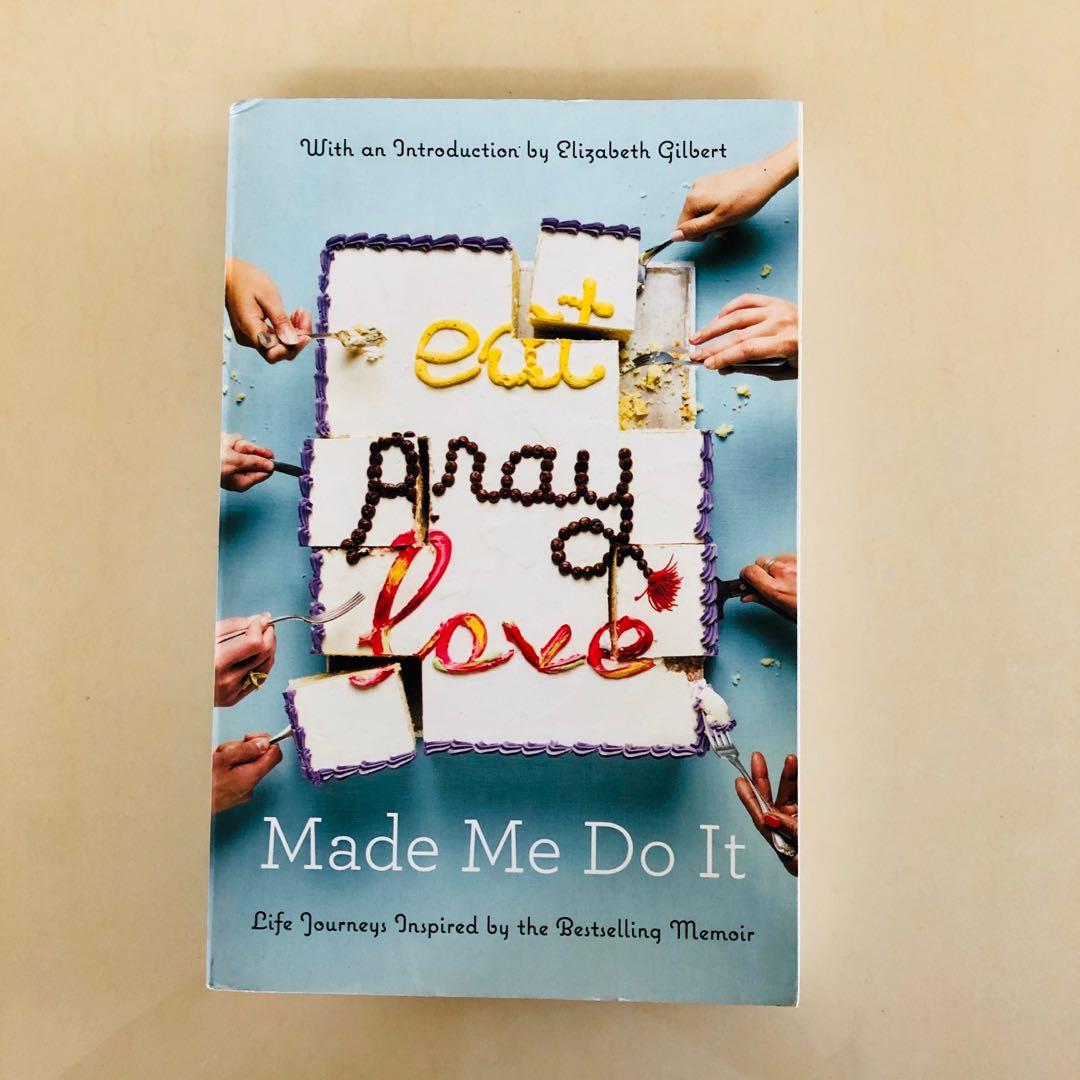

Eat Pray Love helped one writer to embrace motherhood, another to come to terms with the loss of her mother, and yet another to find peace with not wanting to become a mother at all. One writer, reeling from a difficult divorce, finds new love overseas; another, a. Entertaining and enlightening, Eat Pray Love Made Me Do It is a celebration for fans old and new. What will Eat Pray Love make you do? Introduction written and read by Elizabeth Gilbert. Read by Cassandra Campbell, Marc Cashman, Robbie Daymond, Mark Deakins, Ariana Delawari, Jorjeana Marie, and Emily Rankin. From the Compact Disc edition.

In the ten years since its electrifying debut, Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love has become a worldwide phenomenon, empowering millions of readers to set out on paths they never thought possible, in search of their own best selves. Here, in this candid and captivating collection, nearly fifty of those readers—people as diverse in their experiences as they are in age and background—share their stories. The journeys they recount are transformative—sometimes hilarious, sometimes heartbreaking, but always deeply inspiring. In this excerpt, writer Chelsey Everest describes how the book helped her climb out of a debilitating depression.

When I was growing up, my mother had a special, go-to piece of advice for me, one that she rarely suggested to my sisters because with them, it never worked. As an answer to almost all of my anxieties, she told me to “write it down.”

“Write it down” cured high-pitched lunchroom fights with girls at school and assuaged my father’s temper after he’d sent me to my room. It quieted me down when I was bored and performing improv for my mother’s forced entertainment in the middle of a grocery store aisle.

I would write whatever served my purpose at the time: a letter, a journal entry, a short story, a prayer. I wrote and illustrated my first book when I was five, a completely plagiarized, crayon version of Eric Carle’s A House for Hermit Crab.

What We're Reading This Week

Get recommendations for the greatest books around straight to your inbox every week.

There wasn’t much that I couldn’t figure out on paper until I turned nineteen and my doctor told me that I was “mildly depressed.” I wasn’t certain how one measured the extremity of depression or how many degrees separated mildly depressed from clinically depressed from certifiably insane, but I did know that what I’d been feeling was hardly mild. For about a year, I’d found life to be pretty much insufferable. There had been definite factors: I’d just left for college at Boston University, about two hours south of my hometown in southern Maine, and the homesickness was crippling me. The city campus sprawled across the historic Back Bay, bumping up against the Charles River where the crew teams rowed in the fall and spring, and people were everywhere, clambering off the T or filling the crosswalks of Commonwealth Ave. I barely noticed. I had three roommates sharing my penthouse dorm on the eighteenth floor of Warren Towers, overlooking Fenway’s Green Monster and the backed-up traffic on the Mass Pike. Every minute I was surrounded by people, constantly elbow-to-elbow with a hundred strangers, and I’d never felt so alone.

There was also the matter of a cheating high school boyfriend who, shortly after I left, started sleeping with a girl my younger sister knew. She was short and spray-tanned and lied when I messaged her from Boston to ask if they’d been fooling around. After that, every girl looked like a liar. Walking to my eight a.m. lectures, I’d scoff at the girls in high heels, their hair and makeup so perfect that it looked like an entire team had flown in to prep them for class while I donned the same pair of bookstore sweatpants I’d been wearing all week.

I willed my jealousy into loathing, my insecurity into spite. I developed a peculiar brand of hypochondria where a common cold quickly escalated to AIDS; I experienced most of my panic attacks on the elevator up to the eighteenth floor. My anxiety approached in sharply increasing waves, growing to sound-crushing breakers in the matter of a minute. It was a high-pitched wail, a banshee in a bloodstained nightgown with the lungs of a siren.

Eat Pray Love Epub

My depression was different. It was monotone; a sad little crumple of dirty laundry with a face made out of denim pockets. When I tried to explain my depression to my parents, I could never muster the intensity to convey exactly how deep I’d sunk inside of myself. To them, it just didn’t make sense. It wasn’t like I’d experienced some trauma as a child; there was no repressed memory with an uncle or a babysitter, no younger me witnessing a horrific act of violence that robbed me of my older self’s happiness. My life had been sunshine and barbecues, two little sisters who followed me everywhere. There were no issues that couldn’t be solved by writing it down. But there was no writing down depression. The sickness infected my words, left me sounding wounded and numb. Depression became my ball and chain. All I could do was limp along.

So when my doctor told me I was depressed, I decided it was time to take action. I asked her to prescribe me medication. I didn’t tell my mother at first; I knew she’d get a wrinkle in her forehead and ask me if I knew the side effects, the risk of dependency, the chance that I’d begin ideating suicide or lose my sense of humor or become indifferent to life altogether. It wasn’t worth explaining that all of those thoughts had already surfaced on their own. All I wanted were answers; I wanted the misery to be chemical. I wanted medicine to prove that sadness went away.

That summer, after transferring back home to my state school and filling my first prescription of Paxil, I came upon Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love while on a shopping trip with my mom.

“Medicating the symptom of any illness without exploring its root cause is just a classically hare-brained Western way to think that anyone could truly get better,” Gilbert wrote, considering in hindsight her choice to take antidepressants. She’d experienced a nasty divorce, followed by an even more intense affair, and felt herself slipping away from the world in the same slow-motion way that a book falls out of your hands in the moments before you nod off. I knew, because I was feeling that, too. Gilbert sought help in a number of different places and expressed her belief that medication should always be paired with therapy. I loved the idea of therapy, but with a new school only a couple months away, I decided to wait until I could see someone regularly on campus. In the meantime, I read.

Delving into Gilbert’s memoir depressurized my mind; it provided me with sweet relief from the trappings of an anxious heart. I’d waitress in the mornings at a diner on the harbor and spend the afternoons dozing on my mother’s porch swing, reading Eat Pray Love until the Maine mosquitoes reminded me to go inside. Gilbert’s search for wellness became my search for wellness, and by immersing myself in her journey, I started to consider the root causes of my depression. I followed her to Italy and allowed myself to feel full and content even as anxiety replaced my appetite; I joined her in India and copied Buddhist mantras onto Post-its that covered the wall above my bed; and I landed with her in Indonesia and finally, for the first time in a year, allowed myself to wonder about love and why it hurts women so deeply. Scraps of napkin and dozens of dog-eared corners fattened my paperback until it was wider than its binding. I would pore over that book with an intent patience until, hours later, I’d look up from the swing and the sky would be tie-dyed purple, my heart beating slowly and my breath coming steadily. This, I know now, was the closest I’d ever come to actually meditating.

After that summer, whenever I found myself in need of guidance, I’d turn time and again to women’s memoirs. Slowly I began to see patterns in the way that these writers, and women everywhere, dealt with issues of mental health and sexuality. I would think back on the girls from the lunchroom and the girls from BU in their high heels, and I’d feel a prickling along my arms, a hotness in my chest. In those moments, I felt—was it possible?—compassion. It took a few years (and still, it’s rarely easy), but eventually I got to a place where I could begin, again, to write it down. When I turned twenty-five, I enrolled in an MFA program and knew before arriving to my first residency that I would study creative nonfiction and memoir. Now, I facilitate a writing workshop for women. We focus specifically on what has silenced us: what in our lives has left us voiceless, monotone, shrieking or quiet. I urge them to read books by women who have experienced their same pain and come out the other side. I remind them that we all share in suffering. And when one of the writers asks me how I found the courage to write my own difficult stories down, I tell her right away: Eat Pray Love made me do it.

Chelsey Everest grew up in Portland, Maine, and received her MFA from the Stonecoast low-residency creative writing program. She currently teaches English courses at various community colleges and facilitates a writing workshop in the Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania. She resides in Philadelphia with her partner, Tom, and their puppy, Rue.

Eat Pray Love Amazon

Excerpted from Eat Pray Love Made Me Do It: Life Journeys Inspired By the Bestselling Memoir with permission from Riverhead Books.

Image credit: LaVika/Shutterstock.com.